Gear & Review

How does it sound?

Contrary to popular belief, there is only a relatively loose connection between the technical specifications of an audio device and its ability to play music in an authentic fashion. Manufacturers today mostly compete with a range of similar audio devices on the market and need to attract buyers who will mostly be unable to hear the actual product, let alone test it out in their domestic environment, before making their purchase. In this scenario, customers will be comparing the technical specifications of a device rather than the product’s ability to convey the recorded music event with lifelike musicality.

Before the receiver wars of the late 1970s and early 1980s, and even more so before we started comparing prices and purchasing products online, HiFi electronics mostly had to compete with music events and the sounds produced by real-life instruments. Judgement on the performance of audio equipment was based on the ability to satisfy the human ear rather than ultra clean measuring results that would out-spec the competition. Tube amplifiers are a relict of such times, in that they provide more joy to the listener than they do to the reader of their data sheets. Even today, true High End manufacturers will place more emphasis on the subjective human perception of sound than on the objective data that is derived from measurements. Not surprisingly then, the merits of a given audio device are entwined with the personal history and motivation of the people who have spent much of their professional lives to create it.

Turntables

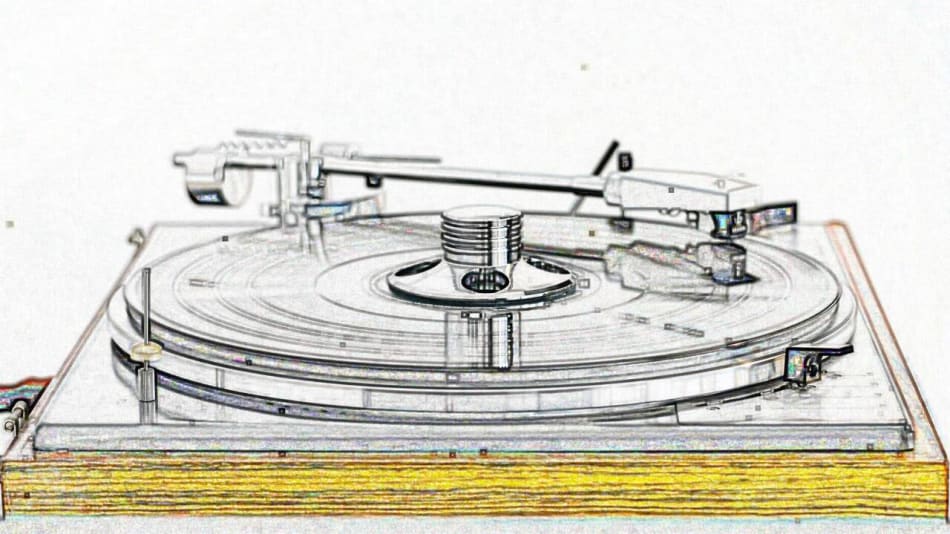

I must confess that I am still a relative ‘newbie’ to the subject of turntables. Like most turntable owners around in the 80s, I was excited about the emergence of the new, super silent, digital technology that came in the shape of a shiny and more compact disc. And, honestly, at the affordable price range of an adolescent, the CD performed much better. I consequently sold my record player in the early 90s, never to look back until ... summer 2018, when we found a 1972 Philips 212 deck in our grandpa’s basement.

Lots of time reading and experimenting has passed since then. The Philips needed a new belt, bracket, and cartridge. We lubricated the moving parts, upgraded the internal wiring, and changed the output terminal from 5-pin DIN to RCA/cinch sockets. We checked the platter speed, corrected the azimuth, as well as the offset and rake angle. We made sure that the turntable was placed on non-resonant footing and was level with the ground. The result is astounding, and for the first time, our turntable actually does sound more impressive than CD, if the record itself is of a good pressing. Since buying a well-engineered LP can be a bit of a gamble, it is a good idea to share personal experience on sound quality, as I have started doing here.

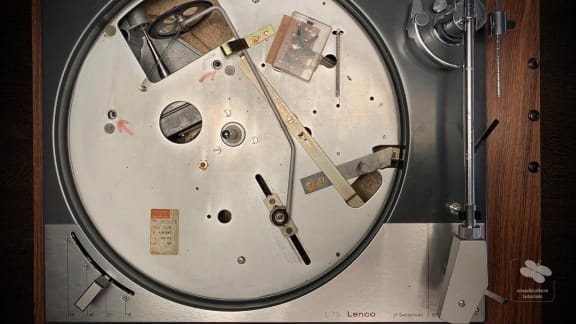

The Lenco shown here was our second project. Once famous as a well-built budget player with surprising sound quality, it arrived here in pretty poor condition. We have had to remove motor noise, bring in new blocks, and adjust the other parameters described above to uncover its potential. The investment of time and effort has not been in vain. For audiophile listening, turntables should not be underestimated.

Dual CS 505-3 Audiophile Concept

Published: 03/02/2022

Manufacturing date: 1987

Author: Karsten Hein

Category: Gear & Review

Tag(s): Turntables

The CS 505-3 is a semi-automatic turntable with full-size suspended sub-chassis that effectively protects the unit's drive mechanism from external vibrations. The 505 features a straight, tubular, high torsion aluminium tonearm measuring just over 22cm in length, and a low-resonance, non-magnetic platter that is driven by a 16-pole-synchronous Dual motor and belt-drive mechanism. The turntable's basic design and layout have been tried and tested and it can, at the time of writing this, still be purchased new, in the form of the revised Dual CS 505-4 that is built by Alfred Fehrenbacher’s Dual Phono GmbH, in the company’s original home town of St. Georgen. The factory is located deep in the Black Forrest, a region famous for its customs, folklore, and precision clockwork mechanisms.

The CS 505-3’s semi-automatic drive unit is easy to operate. Moving the tonearm in position over the record will automatically set the platter in motion at the pre-selected speed. The tonearm initially remains in raised position, until a lever is flipped to gently put it down. The platter stops spinning automatically when the stylus reaches the end of a record, and the tonearm is automatically raised once again. On our unit, there was a mild plopping sound as the turntable shut off. It was probably caused by the tonearm lifting rather abruptly. However, this is just meant as an observation and not as complaint. I was at first a little surprised by the phenomenon, but it never really bothered me. The tonearm remains raised and then needs to be returned to the start position by hand.

In 1987, the first CS 505-3 sold for just under 500.00 DM, (96.00 GBP) and modern customers of its successor, the CS 505-4, are once again asked to pay the same in euros. This might seem a bit pricey in both cases. However, having listened to the CS 505-3 perform in our living room for some days, I feel it is still quite a good deal. More so than our Sansui 525, the Dual with its original ULM 65 E cartridge and elliptical diamond stylus had me listening to one record after another, enjoying its charming sincerity and musical drive. But what was it exactly that enthralled me?

Advert eiaudio/shop:

I have always been fond of the Thorens 318 turntable design for getting the balance between technical sophistication and elegant understatement right. As if its engineers had taken their pointers from Japanese furniture design, more so than the tech-savvy Japanese electronics industry ever had by itself. And I found very similar design choices to be present in the Dual CS 505-3, especially in combination with its black, wooden plinth. Sadly, most turntables of those days still featured permanent interconnects which made it difficult to make adjustments to the sonic balance by means of connection alone. I would have loved to attach my favourite silver solid-core cables, of course.

The ULM 65 E was the original Dual cartridge for the 505-3 to which an Ortofon-made, bonded, elliptical, diamond stylus was attached. The ULM was not a High End cartridge and only offered a limited frequency bandwidth of 10-25,000 Hertz. Channel separation was also not impressive at 20dB. And still, it offered considerable output rated at 4 mV. This suggested that it could play loud. The combination of cartridge, stylus, and drive unit worked quite well, but also showed some obvious weaknesses that one could find either off-putting or endearing, case by case.

I first whipped out a bad pressing of Norah Jones’ album “Come Away With Me”, and was disappointed that the Dual’s elliptical stylus brought out lots of sibilance that our Sansui 505 with AT VM 95 ML cartridge had so well hidden. This was not surprising perhaps, considering how deeply the micro-linear stylus of the AT could reach into the groove. The record sounded worse the closer the stylus moved to the centre. I next put on Stacey Kent’s album “I Know I Dream” and was surprised by a pleasant forward drive and rhythm that instantly made me tap my foot. I loved how Stacey’s voice seemed stronger, more direct, and also more engaging than I was used to. The music sounded slightly less delicate and did not reveal transients so well, but I did not miss this somehow.

The Dual’s ferocious and rhythmically engaging character had me smiling several times though the album. “I Know I Dream” being a good pressing, I had no issues with sibilance whatsoever. I noticed that voices were perhaps not revealed in the most authentic fashion and could sound a little “vintage” at times. They did not manage to free themselves from the instruments as much as I was used to, but, in the overall scheme of things, were endearing and lots of fun to listen to. If I had first thought about replacing the permanent interconnects with RCA jacks and upgrading the cartridge to a modern one with a more sophisticated stylus and better specs, every time that I came back listened I decided that any updates or upgrades could wait for another day.

Dual Company History

Christian and Joseph Steidinger started out as a manufacturer of clockwork and gramophone in the German Back Forest town of St. Georgen in 1907. The original company simply bore the family name, until they rebranded as Dual in 1927. The new company name was chosen in reference to their signature “dual-mode” power supplies in which they were true pioneers. Gramophones featuring these supplies, could either be powered by electricity or wound up for playback. Given their early success as a parts supplier, the Steidinger brothers began designing their own turntables.

During the German economic recovery that followed World War II, Dual became the largest producer of turntables in Europe. The German economy still enjoyed a price advantage over the rest of Europe and became known for high-quality once again. The Steidinger brothers had to hire up to 3,000 factory staff in order to keep up with the growing demand in entertainment devices in the world. Although Dual stretched the brand into other consumer electronics items, their turntables have remained iconic to this day.

The original Dual company went bankrupt in the early 1980s, following a decade of fierce competition from cheap and sophisticated imports from Japan. It was sold to the French electronics group Thomson SA. In 1988, the German company Schneider Rundfunkwerke AG bought Dual and then spun off the ‘Dual Phono GmbH’ to Alfred Fehrenbacher in 1993. Fehrenbacher produces Dual turntables 'Made in Germany', in the Black Forest town of St. Georgen, based on Dual’s original product lines until this very day.

Specifications

- Concept: suspended chassis, belt-drive

- Drive unit: 16-pole-synchronous motor

- Motor type: Dual SM 100-1

- Power consumption: 8 Watts

- Platter: non-magnetic, 1.2 kg

- Platter speeds: 33 1/2 and 45 RPM

- Pitch control: +/- 6%

- Wow and Flutter: 0.06% (WRMS 0.035%)

- Rumble: 52 dB (75% weighted)

- Channel separation: > 25 dB

- Channel balance: < 2 dB

- Arm length: 221 mm

- Offset angle: 24” 30’

- Tracking error: 0,15 “/cm

- Cartridge type: Dual ULM 65 E

- Cartridge system: moving magnet (MM)

- Stylus model: Ortofon DN 165 E

- Stylus type: elliptical diamond, bonded

- Tracking force: 15 mN (10-20 mN)

- Frequency range: 10-25,000 Hz

- Output: 4 mV / 5cms (1,000 Hz)

- Compliance: (h) 25 um/mN; (v) 30 um/mN

- Cartridge weight: 2.5 g

- Total capacitance: 160 pF

- Dimensions: (W) 437mm; (D) 369mm; (H) 138mm

- Weight: 6kg

- Country of manufacture: Germany

- Year(s): 1987-1990

Dual CS 630Q

Published: 16/03/2023

Manufacturing date: 1983

Author: Karsten Hein

Category: Gear & Review

Tag(s): Turntables

I confess that, when the Dual CS 630Q was brand new on the shelves during the early 1980s, I would have walked straight past it, only to marvel at the cleaner-looking and trendier Technics decks from Japan. And the sad demise of the Dual company alongside many other German manufacturers of quality audio gear during that same period suggests that I was not alone in this assessment. 40 years later, I am sitting in our studio listening to one Dual turntable after another only to find that we had been utterly wrong in ignoring them. But, as so many times in the history of mankind, we are only smarter after the fact.

During the 1980s, I was a teenager who had to stretch his allowance. More often than not, the money for HiFi gear came from my father. I mostly liked what my friends at school liked and what I was able afford. And this is also my excuse for purchasing a JVC AL-F3 as my first turntable, a mass-produced fully automatic direct-drive deck in plain black that can be found in mint condition for EUR 20.00 on ebay these days. Sellers of the Dual, on the other hand, usually for at least five times as much for their machine regardless of its condition. The trouble for Dual was that both turntables played music, and, as most people did not have the time, expertise, or equipment to compare the sound of turntables, the difference between the devices was a matter of marketing.

Japanese turntables often boasted the latest in technology, even before it was proven that this actually served the purpose better than established means. The S-shaped tonearm, turntable automation, and direct drive technology were cases in which German manufacturers were slow to follow the hype. The ULM tonearm, for example, did have excellent tonal and rhythmical characteristics on the Dual turntables. It was lightweight and torsion-free by which it could offer a forward drive that feels natural in music. Earlier idler wheel turntables and some well-engineered belt drives could very well compete with newer direct drive models and have remained favourite classics in many audiophile communities. And turntable automation has long since outlived itself, with modern decks often only having a single switch that is required to set the motor speed.

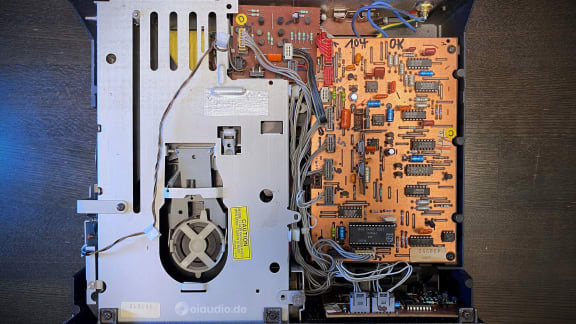

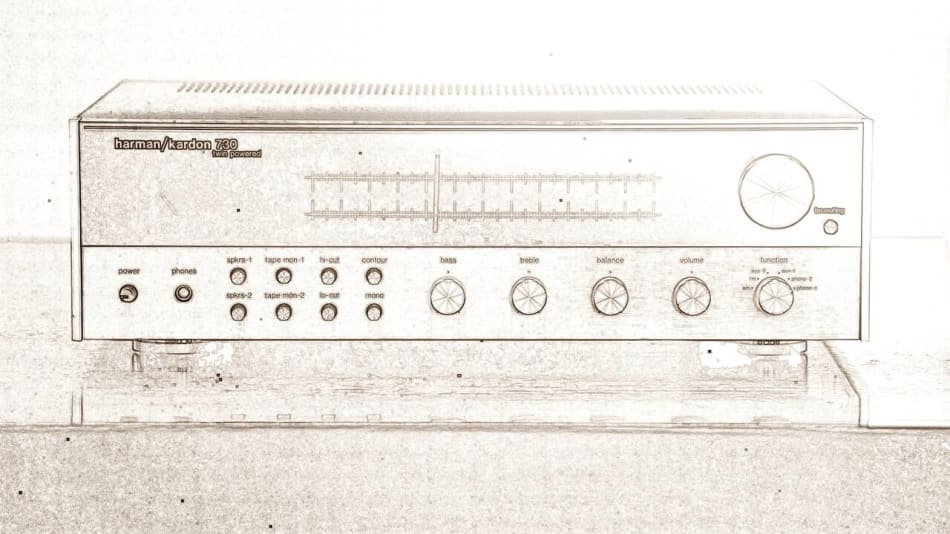

While Dual and other German manufacturers were seemingly out-classed in the 1980s, listening to the old decks perform suggested that they were still excellent choices when it came to their musicality, especially when played within a well-set-up system. The Dual CS 630Q that is presented here was handed down to my daughter from her recently deceased great aunt along with some other mid-Fi gear. Among the items were a Dual CV 1260 receiver (manufactured by Denon), a Dual CT 1260 tuner that was connected via 5-DIN plug, a Denon DCD 660 CD player, and two Canton GLX 100 bookshelf speakers that served to wrap up the ensemble. And, as the equipment had been sitting on a shelf for some years, I wanted to take the opportunity to run some routine checks and to present it in this forum.

Among these new devices, the CS 630Q interested me the most. I was already a great fan of the earlier and more elaborate Dual CS 721, for which I had built a walnut plinth for improved drive isolation. The CS 630Q was claimed to offer an improved signal-to-noise ratio paired with a more modern look. Where the famous Technics decks had a visible strobe light that reflected on iconic dots along the platter rim, Dual featured an accurate LCD display that interpreted the speed reading electronically. Dual’s legendary 4-point gimbal rested on adjustable tip bearings and served to stabilise the straight ultra-low-mass (ULM) tonearm well. The Start, Stop, and Lift buttons felt firm and gave great sensory feedback, and I also enjoyed the fact that the rotation speed adjustment was executed in the same manner. The record size was set separately via a selector switch located to the right of the tonearm. All in all, this seems like a well thought out design.

Modern users might object that the layer’s surface was not flat but instead showed all kinds of elevations and crevices. On the other hand, these oddities gave the CS 630Q its low silhouette and recognisable appearance. While I would not perhaps have thought of purchasing this Dual for myself, I did enjoy the look of it while it was perched on our makeshift audio sideboard with our experimental system in the studio. The system consisted of the Dual CV 1260 integrated amplifier and our Epicure 3.0 loudspeakers that had already shown that it worked very well together when playing from a CD source. I did have some difficulties adjusting the tracking force, because the automatic features got in the way of performing the action: Moving the arm towards the platter started the motor, and taking the Dual off the power grid automatically elevated the arm. There seemed to be no way out of this predicament, and I ended up adjusting the raised arm by also raising the tracking scales, which was probably not the most accurate method.

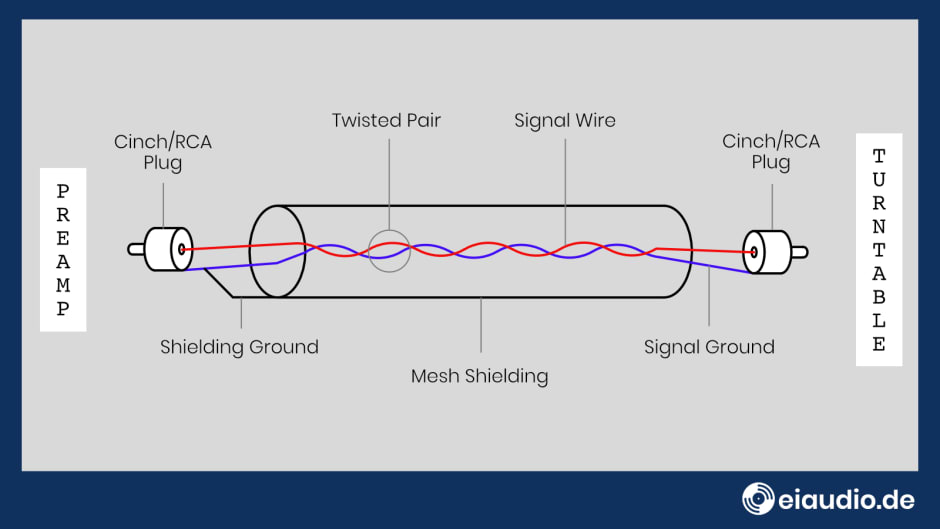

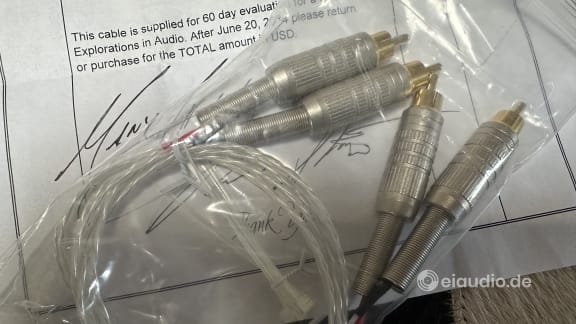

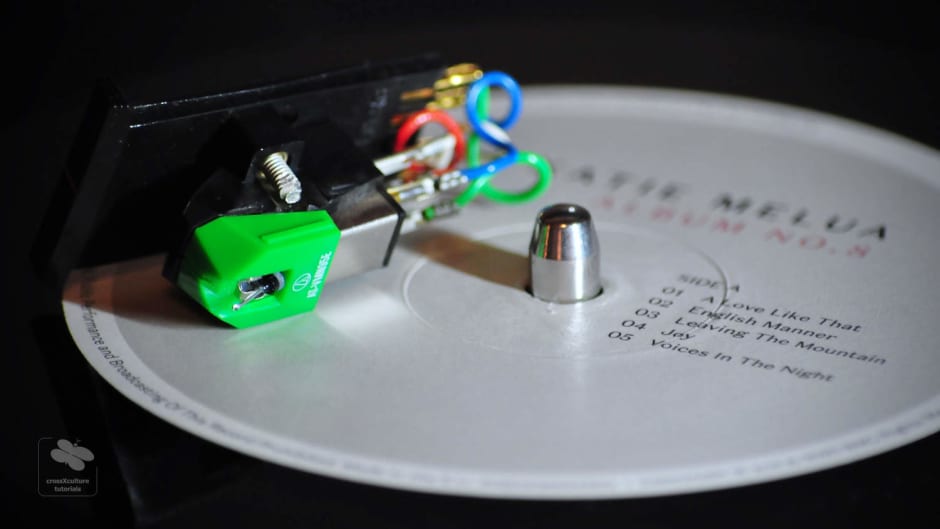

My reason for wanting to confirm and set the tracking force was due to an error that I could hear as sibilance on the inner LP tracks. The original ULM 66E cartridge had been replaced with an Ortofon DN 166 E which still seemed to work alright. I started my explorations with Fleetwood Mac’s 1977 album Rumours, of which I had the 2009 pressing. For a 70s album, Rumours offered a decent recording quality, as well as a wide range of songs that varied both tonally and rhythmically. Listening to the album with the CS 630Q for the first time, I also notice a humming that sounded like a grounding issue. I inspected the original cinch plugs and found that the metal grounding had corroded. The original plugs were already quite cleverly designed featuring a broken outer ring and a split centre prong. I decided to replace them with some decent modern standard Neutrik Rean, which were much less sophisticated in terms of sonic virtues, except for their debatable gold-plating, perhaps.

Looking at stylus options for the ULM/Ortofon cartridge, I came across the elliptical stylus that was now in place for about 75.00 EUR and then found the complete headshell with cartridge and Shibata stylus for just 14.00 EUR more. For my daughter learning to play records for the first time, the present stylus would do, but if this turntable had been mine for the keeping, I would have gone for the ‘Ortofon OM PRO S SH4 bl hs’ full package as advertised on the Thomann website, among others. For the time being, I set the tracking force with the scales on a CD case next to the rotating platter to 1.05g and the anti-skating to approximately half this value. I noticed that the Ortofon cartridge started to muffle the treble when the tracking force exceeded 1.25g. The original sibilance might have been caused by the anti-skating force exceeding the tracking force when, really, the opposite should be the case.

Fleetwood Mac’s album Rumours had started to sound just right, with a good amount of drive and swing. I enjoyed the amount of detail presented by the elliptical stylus, but I could also hear its limitations in terms of treble nuances. The higher the tone, the more it seemed to blend in with other high tones playing in the recording. This gave the music a robust and danceable presence rather than an audiophile experience. Bass on the other hand was tight and layered. I was able to get a good feel for the different materials of the drum set that stayed quite separate of the other instruments in “Don’t Stop Thinking About Tomorrow”. At the same time, I was missing some of the genuinely low bass frequencies that would have served the overall music impression well.

Considering the fact that the Dual CS 630Q already had a universal headshell mount, there was a wide range of cartridges available for the arm that were easy to swap and experiment with. While setting the tracking and anti-skating correctly improved the sibilance on the inner tracks, I was not able to eliminate it completely using the old stylus. The straight arm’s tracking error of 0.15° was, at least in my opinion, not large enough to explain the extent of the phenomenon. And it was sad as well, because “Songbird” was among my favourite tunes on the album. If I could only trust our kids and their friends (and the friends of their friends) to keep the stylus free from harm, I would be tempted to take that Ortofon SH4 offer.

Specifications

- Type: direct drive turntable

- Features: Fully automatic, with PLL quartz lock

- Microprocessor type: EDS 910

- Platter type: non-magnetic, removable

- Platter dimensions: (D) 304mm x (H) 10mm

- Platter weight: 1,170gr (700gr, without matt)

- Speeds: 33.33 and 45rpm

- Pitch-control: 30-36 RPM / 42-48 RPM

- Wow and flutter: +/- 0.035%

- Signal to noise ratio: 80dB, weighted

- Tonearm: distortion free ultra-low-mass tubular aluminium

- Gimbal: 4-point tip bearing

- Effective tonearm length: 211 mm

- Offset angle: 26°

- Tangential tracking error: 0,15°

- Headshell overhang: 19.5 mm

- Original cartridge: Dual ULM 66E

- Stylus-replacement: DN 166E

- Stylus-type: biradial diamond

- Tracking force: from 1 to 1.5g

- Frequency response: 10Hz to 28kHz

- Power consumption: 12,5 watts

- Compliance: (h) 35 / (v) 30

- Original cartridge weight: 2.0 g

- Dimensions: (W) 440mm x (H) 111mm x (D) 364mm

- Total weight: 5.5 kg

- Country of manufacture: Germany

- Year(s): 1983 - 1986

Dual CS 721

Published: 27/07/2022

Manufacturing date: 1976

Author: Karsten Hein

Category: Gear & Review

Tag(s): Turntables

The CS 721 was Dual’s flagship turntable towards the end of the 1970s and is, by many, considered to rank among the best Dual turntables ever made. When there is disagreement between the experts, this is usually about the merits of the drive system. Proponents of idler wheel turntables, the ‘Treibrad Classics’, would cite Dual models CS 1219 and CS 1229 as their favourites, whereas belt-drive fans would give preference to the CS 5000 or CS 7000 Golden. The CS 721 was a direct drive design (DD) and, in all fairness to the other two camps, had the most audiophile specifications in terms of rumble, wow, and flutter of them all. However, we do not listen to specifications but to music, of course. And I must confess that I do love the straightforward sound of our smaller CS 505-3 as well.

In its most affordable form, the CS 721 was not the most beautiful deck on the market. Its plinth was a base of cheap plastic that was skirted with a frame of laminated wood. Dual had to rely on its good name in audiophile circles in order to be able to sell its products next to the sleek and slim looking Asian designs from Technics, Pioneer, Sony, etc. In fact, the new lack of genuine wood on the products of the German manufacturer from the Black Forest was already a tribute to the increasingly price-driven market. However, the pressure to surpass its competition by means of sophistication assured the CS 721 some highly sophisticated features that are rarely found on turntables of any age.

One obvious highlight of the CS 721 was its tonally rich made-for-Dual Shure V15-III cartridge with its Super-Track-Plus stylus. The Shure V15-III was an excellent tracker with a low stylus force of merely 0.75g to 1.25g. The cartridge exhibited the usual Shure bass qualities while performing smoothly across an extensive frequency range from 10 Hz to 25,000 Hz. Sadly, the original Shure stylus was too worn out on our model, so that I had to look for a suitable replacement. My first impulse was to take the plunge on a Jico SAS stylus with boron cantilever; however, an indefinite delivery impasse from Jico forced me to settle for a Tonar Shibata stylus instead. Shibata needles were originally developed for use with quadrophonic recordings, reached deeply into the record groove, and, similar to Jico’s SAS styli, were capable of great nuance. However, listening to the two styli in direct comparison, it was hard not to favour the worn-out Super-Track-Plus for its amount of delicacy.

I also decided that I was going to improve the plinth of the turntable to isolate any physical vibrations from the floating chassis, as the thin plastic vat did not seem sufficient for the job. You will find a full article on the project in the 'Explorations' section of this blog. The result was a solid wood plinth that held the original structure suspended whilst silencing any vibrations to the plastic through the use of rubber foam. I used tri-ball absorbers to further isolate the plinth from potential vibrations caused by steps, slamming doors, or the other Hi-Fi units in the rack. The result was a tonally rich, precise, and undisturbed sound, just as one would expect from one of Dual’s top players.

Next to its precise and quiet motor, rigid tonearm, and legendary Shure cartridge, the CS 721 offered a host of adjustable settings that were class-leading at its time. Like all Duals of this period, it offered three transport screws to clamp down the chassis during transport. I always loved this feature on the Dual decks, as I had to spend lots of time transporting them in the car. Even the dust cover lift could be adjusted on the CS 721 just in case the spring should soften with age. The tonearm had a 2-fold dampened, adjustable counterweight and could additionally be altered in lateral length to perfectly accommodate most cartridge weights.

The vertical tracking of the CS 721 tonearm could be calibrated via a lever. Most other turntables only offered socket screws for the purpose. In a similar way, one could adjust the lift angle and the precise touchdown position of the stylus on the record groove. The touchdown speed could be adjusted to suit the weight of the cartridge. It was interesting to note that the manual lift function was not affected by adjustments to the lift height, as this, too, was set via a separate control. When playing back records, the CS 721 could be set from single to infinity mode, by which it would repeat playing a record until it was manually interrupted. When taking a closer look at the headshell, I was surprised to find that the cartridge was clamped into position and additionally secured by two screws. I learned that there had been two headshells sold of which only one could be adjusted. So I ended up purchasing an additional TK-24 headshell to have more freedom in my settings.

While the tonearm was adjusted by changing the lateral length of the arm and then via the knurled ring of the counterweight, a further adjustment ring was available to set the stylus down force. In combination, this was one of the most sophisticated settings I had ever seen. Anti-skating could be adjusted to suit conical and bi-radial styli. It was conceivable that the CS 721’s vast combination of settings would have been more confusing than helpful to some owners. On the other hand, listening to records had always been similar to fly fishing, with lots of time, skills, and effort needed to achieve a somewhat short-lived result. In other words, the Dual was anything but plug-and-play. All the more, it was gratifying to own and listen to, once the perfect setting was achieved, especially with its new walnut plinth.

Related Articles:

< Constructing the Plinth | Dust Cover Restoration >

Dual Company History

Christian and Joseph Steidinger started out as a manufacturer of clockwork and gramophone in the German Back Forest town of St. Georgen in 1907. The original company simply bore the family name, until they rebranded as Dual in 1927. The new company name was chosen in reference to their signature “dual-mode” power supplies in which they were true pioneers. Gramophones featuring these supplies, could either be powered by electricity or wound up for playback. Given their early success as a parts supplier, the Steidinger brothers began designing their own turntables.

During the German economic recovery that followed World War II, Dual became the largest producer of turntables in Europe. The German economy still enjoyed a price advantage over the rest of Europe and became known for high-quality once again. The Steidinger brothers had to hire up to 3,000 factory staff in order to keep up with the growing demand in entertainment devices in the world. Although Dual stretched the brand into other consumer electronics items, their turntables have remained iconic to this day.

The original Dual company went bankrupt in the early 1980s, following a decade of fierce competition from cheap and sophisticated imports from Japan. It was sold to the French electronics group Thomson SA. In 1988, the German company Schneider Rundfunkwerke AG bought Dual and then spun off the ‘Dual Phono GmbH’ to Alfred Fehrenbacher in 1993. Fehrenbacher produces Dual turntables 'Made in Germany', in the Black Forest town of St. Georgen, based on Dual’s original product lines until this very day.

Specifications

- Turntable type: Fully automatic

- Motor: direct drive, electronically controlled

- Motor type: Dual EDS 1000-2

- Speeds: 33.33 and 45rpm

- Platter weight: 1.5 kg, aluminum die cast

- Platter weight with rotor: 3.0 kg

- Platter size: 305mm, dynamically balanced

- Pitch control: +/- 10%

- Wow and flutter: < 0.03%

- Rumble: > 70dB

- Tonearm: extended tubular, 2x damping

- Tonearm effective length: 222mm, height adjustable

- Cartridge: Shure V15 III (1973 - 1987)

- Stylus pressure: 0.75 to 1.25g (1.0g)

- Stylus type: Microline, elliptical diamond

- Channel separation: 28dB @1kHz

- Frequency range: 10 - 25,000 Hz

- Cartridge inductance: 500 mH

- DC resistance: 1,350 Ohms

- Resistance: 47 kOhms

- Output: 3,5 mV @1kHz

- Cartridge weight: 6.0 g

- Turntable Weight: 7.8 kg

- Dimensions: (W) 424 mm x (H) 150 x (D) 368 mm

- Country of manufacture: Germany

- Year(s): 1976 - 1979

Lenco L75

Published: 31/05/2020

Manufacturing date: 1967

Author: Karsten Hein

Category: Gear & Review

Tag(s): Turntables

Fritz and Marie Laeng founded the Lenco turntable company in Burgdorf, Switzerland in 1946. The name Lenco was derived from the Laeng’s family name, largely due to Marie’s initiative. In the time before turntable production in Burgdorf, the Laeng couple had already been fascinated with audio technology and had been running an electrical business since 1925. The Laeng’s genuine enthusiasm for sound reproduction resulted in reliable quality products and excellent service for the few units that were returned to the factory for reworking. Lots of passion, high quality, and excellent service proved to be a solid foundation for success, and the company soon opened a second factory in Italy to satisfy the growing demand.

Lenco partnered with specialist companies in the production of accessories that they could not easily produce themselves. Komet was a specialist for tube amplifiers and supported Lenco in producing turntable & amplifier combinations. Another, perhaps more famous, partner was Goldring, a specialist manufacturer of phono cartridges. Some Lenco turntables were marketed bearing the Goldring logo. In doing so, the lesser known Lenco of Switzerland was able to benefit from Goldring’s established sales network, a circumstance that made it easier for Lenco to reach out to customers around the globe. Within just a couple of years, Lenco was able to generate sales in more than 80 countries.

Sadly, Marie Laeng died at a particularly vulnerable time for the company, during the oil crisis of 1974. She had been the heart and soul of the operations, and the business was now simultaneously hit from at least two directions: a declining global economy and the loss of their chief motivator. A third hit was then caused by the influx of cheaper priced electronics from newly rising Asian countries that turned out to be the winner of Europe’s new price driven economy. Lenco AG Burgdorf declared bankruptcy in 1977, with the newly formed Lenco Audio AG taking over existing service agreements and completing what was to be the final generation of Lenco products.

The Lenco L75 was built from the early 1970s and designed to meet the challenges of a price driven market. Just affordable enough to be purchased by university students, it was designed with the intention of bringing audiophile sound quality made in Switzerland to a young consumer group. Despite the ever so slight rumble coming from the sturdy idler wheel drive construction, the woodcased Lenco included some welcome features, such as a floating cabinet, a newly designed tone arm with visible anti skating weight, and four playing speeds ranging from 78 RPM all the way down to 16 RPM. Available accessories included a strobe speed control disk for fine adjustment, a record sweeper with fixture on the deck, and record clamps to reduce vibrations. Today, the L75 ranks among the best idler turntables ever made. Especially audiophile listeners hold the L75 in high esteem, knowing well that even the considerable success of the L75 in the end was not enough to save the failing company from extinction.

< Tri-Ball Absorbers | Vinyl-Singles Puck >

Specifications

- Drive: Idler drive

- Motor: 4-pole synchronous with conical axis

- Speeds: 78, 45, 33-⅓, 16-2/3

- Wow and Flutter: ±0,08% / ±0,4%

- Rumble: 36 dB (unweighted); 60 dB (weighted)

- Plater: 306 mm, 3,7 kg, Zinc-alloy

- Tone-arm length: 227 mm

- Overhang: 17 mm (adjustable)

- Offset Angle: 23°12' (±0,8° max.)

- Material: Tubular Aluminium

- Stylus pressure: 0,5 g

- Dimensions: 445 x 335 x 150 mm

- Weight: 10,5 kg

- Country of Manufacture: Switzerland, Italy

- Year(s): 1967 - 1985

Philips 22 GA 212 Electronic

Published: 19/05/2020

Manufacturing date: 1972

Author: Karsten Hein

Category: Gear & Review

Tag(s): Turntables

Built from 1971 to 1976, the Philips 22 GA 212 Electronic turntable is still considered to be among the best Philips turntables ever made. Better known as Philips 212, the unit has achieved somewhat of a cult status among vinyl fans and vintage collectors. Key features include a floating suspension of the platter and sub chassis that provides excellent shock protection and capacitive touch keys featuring green backlights. The unit shown here was built in 1972 and, with some maintenance, is still running smoothly without any audible noise coming from the bearings or motor.

The floating sub chassis results in a very low rumble value, and the light weight aluminum platter works quite well and does provide an interesting alternative to the more common approach of providing more mass to the platter and chassis. Playing speeds are set at 30 and 45 RPM and pitch can be independently (!) adjusted for both speeds. The Philips 212 came fitted with Philips’ own GP400 cartridge which was durable but little adapted to audiophile needs. The company’s own upgrade was the GP401 which offered greater sonic accuracy and detail.

On the unit shown here, the GP400 was replaced by an Audio-Technica at-VM 95 E pickup. The Philips 22 GA 212 headshell can easily be removed by pulling it out forwardly from underneath the tonearm bracket along with the wiring. A welcome feature, for owners who wish to have multiple cartridges at hand. The modern Audio-Technica easily outperforms both the GP400 and GP401. It provides an honest well-detailed and lavish sound, perhaps with a slight tendency to sounding unrefined. There are better cartridges in the Audio-Technica range, all of them being quite affordable, but considering the lightweight tonearm’s limitations of adjustment and control the VM 95 E is certainly a risk free choice. The original 5-pin DIN plug on this unit was replaced with Neutrik cinch/RCA connectors.

Specifications

- Speeds: 33 and 45 RPM

- Automatic speed control: internal strobe light

- Manual speed adjustment: +/-3%

- Rumble: < -62 dB (DIN B)

- Wow and flutter: <0.1%

- Tonearm length (axis to stylus): 221 mm

- Cartridge: Super M 400

- Optional phono preamplifier: GH 905

- Voltage rating: 240 V AC switchable, 5 W, 50 Hz

- Dimensions: 39x14x34 cm

- Weight: 7 kg

- Country of manufacture: Germany

- Year(s): 1972 - 1975

Sansui SR-525

Published: 02/02/2021

Manufacturing date: 1976

Author: Karsten Hein

Category: Gear & Review

Tag(s): Turntables

Following the sale of our Tannoy DC6t speakers to a fellow audiophile in northern Germany, I again had some money to spend on explorations. Looking for improvements to make on our HiFi setup, I decided that much could be gained from upgrading the record player on our main system. While our Philips GA 212 still put out a solid performance, its tonearm and chassis did have some limitations in terms of cartridge upgrades, etc. For vinyl to sound even better, it was high time to change to a more sophisticated concept altogether.

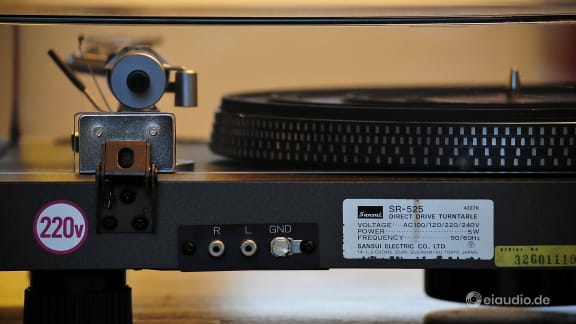

I scanned the web for vintage offers and asked friends for suggestions. Among our choices were the typical Dual, Thorens, Denon, Technics and Micro Seiki brands, all offering well-known classics in their own right, but none of the more affordable ones looked attractive to me, until I came across an unlikely contender in the upper mid-market segment, the Sansui SR-525 DD. Based on a similar chassis and tonearm design as Sansui’s SR-323 belt-driven turntable, the SR-525 offers some significant upgrades, such as the quietest direct drive motor of its time and a quartz speed control with built-in strobe light. The technology is state of the art, especially for a 1976 machine, and I have read nothing but praise about this player.

This is no surprise, really. The Sansui Electric Company was founded by Kosaku Kikuchi in Tokyo, Japan in 1947. Similar to many of his contemporaries, Kosaku cut his teeth in the industry by manufacturing transformers and simple radio parts, until he realised that fluctuation in the quality of components was making it difficult for manufacturers to consistently assemble high quality devices. Kosaku therefore determined that Sansui should prioritise product quality over manufacturing cost. Later, as Sansui diversified into more complex products, this focus on quality proved to be beneficial to the reputation of the brand.

By 1954, Sansui was manufacturing preamplifiers and amplifiers that were sold both as kit for home assembly and as finished product. Although the first units were based on mono tube designs, stereo tube systems were introduced in 1958. By the mid-60s, Sansui’s internal and external design choices had earned the company a solid reputation for high quality audio products. It was at this time that the company started producing its iconic black-faced AU-series amplifiers. Among these were to be found many units that can well be classified as ‘High End’ and remain much sought after by audio enthusiasts until this day. The company produced its first turntable in 1967, a full nine years before the SR-525 came to life.

I found our SR-525 at a vintage HiFi dealer in Mannheim called ‘Goldladen’, combining the family name of its owner with the German word for shop. And although I had to pay a little extra for buying from a proper retailer, I liked the idea that I could drive there and inspect it, before making a purchase. Upon arriving at the shop, I found the Sansui to be in absolutely mint condition. With the platter raised, it was impossible to tell, if the motor had ever run, and there were hardly any scratches on the cover either. Standing in front of the SR-525, there is very little in its design, touch, and feel that makes it out to be a vintage player. In its simplicity and dark grey paint coat, it rather resembles the players around the turn of the century. The only item that gives it away are the clunky rubber feet, perhaps. But they do a fabulous job in keeping the record from skipping.

The tonearm is of sophisticated design with a suspended anti-skating weight and an additional lateral weight to keep resonances at bay. Its S-shape assures that the stylus angle is nearly perfect over most of the record’s surface. The Sansui’s total weight of nearly 10kg provides a solid base to absorb vibrations of any kind. At its original German sales price of 865,00 DM, it was nearly 200 DM more expensive than the belt-driven Philips, and this really shows. Other models in the SR series were the belt driven 323, the similar but wood finished 626, and the higher specced 929.

Do you have some personal experience with Sansui turntables? Please feel free to share your thoughts in the comments section below. Your perspective will be highly appreciated.

Specifications

- Type: manual direct drive turntable

- Platter: 310mm, die-cast aluminium alloy, 1,4kg

- Motor: 20-pole, 30-slot DC brushless

- Speeds: 33 and 45 RPM, servo-controlled

- Wow and flutter: < 0.03% WRMS

- Signal to noise ratio: > 64dB

- Rumble: > 72dB

- Tonearm: statically balanced, s-shaped, resonance-free, adjustable height

- Effective length: 220mm

- Overhang: 17,5mm

- Cartridge weight: 4 to 11g

- Dimensions: 46,9 x 15,0 x 37,5cm

- Weight: 9.5kg

- Year(s): 1976 - 1978

Purchased at:

www.goldladen-mannheim.de

Laurentiusstraße 26

68167 Mannheim

Tel.: 0151 241 643 55

Technics SL-1310

Published: 25/04/2021

Manufacturing date: 1975

Author: Karsten Hein

Category: Gear & Review

Tag(s): Turntables

Following the stellar performance of our 1977 Sansui SR-525 direct drive turntable, I began scanning the web for other direct drive contenders from the 70s. And, since Technics had been the company to invent the direct drive concept, I was curious to learn how their turntables compared against the formidable standard set by our Sansui. By the 1970s and 80s, Technics decks had earned a reputation for being at the cutting edge of turntable technology. In addition to introducing and refining the direct drive, a design by which the motor shaft itself serves as the axis of the turntable platter, Technics was also credited with being among the first manufacturers to bring the sophisticated S-shaped tonearm to the mass market. I therefore decided that a Technics deck would be a worthy contender for exploration.

The brand’s most iconic turntable is arguably the SL-1200. To my knowledge, it is also the longest turntable in production. It first came out in October 1972, just one month after I was born, and continued to be in production until 2010. After a six-year break during the vinyl crisis, production resumed in 2016. Although primarily intended as a high fidelity consumer record player, the SL-1200’s superb build quality and high torque motor made it an instant success with radio stations and club disk jockeys. To date, more than 3 million units of this player have been sold. And, considering that it is back in production, we are still counting. Perhaps it is no surprise then, that an SL-1210 turntable is on display at the London Science Museum, as one of the icons that have shaped our modern world.

Since so much had been said and written about the SL-1200, prices for them used were quite high at my time of searching. This was even true for specimens that were in relatively poor shape and had been dragged around clubs, etc. Regardless of the condition, the name alone seemed to validate a higher price. I therefore decided to look for Technics turntables that offered a similarly sophisticated design but were missed by mainstream attention. I soon learned that the Technics 1310 offered much of the same technology that is found on its famous sibling, but this at a far lower price tag. And, due to its mostly domestic use, chances of this player having been dragged from club to club were rather slim. It appeared to me that the major differences between the two decks rested on their ability to absorb chassis resonances, to maintain exact speed in the event of physical force against the platter, and in the stress resistance of their lower chassis. In all these disciplines, the SL-1200 clearly had the upper hand.

And still, the SL-1310 can rightfully be considered an audiophile record player, even if it was not built to be carried around as a professional DJ or radio player. For my intended usage in our domestic environment, the SL-1310 had all the relevant features without the high price tag of its sturdier sibling. I began to narrow my search to the SL-1310 and noticed that cracked lower chassis were the norm rather than the exception. It seemed to me that the combined weight of the aluminium top casing and platter were simply too much weight for the lower plastic chassis to carry, especially when the Technics was moved carelessly. Other specimens had ugly scratches along the front or showed some discolouration of the body paint where they were mostly touched. Some had missing or broken dust covers, faulty mechanisms, or were simply missing the cartridge or stylus. On the positive side, most of these symptoms were relatively easy to spot. I therefore decided that I would focus on SL-1310s that were visually intact and would then see to it that functionality was properly restored.

The specimen that I ended up buying seemed to offer both. Its body and cover were in excellent condition with just a tiny hairline scratch at the front. It was still fitted with the original Shure M75 cartridge and ED stylus, a clear indication that this player had not been used much. There was no damage to the lower plastic body. The price still was relatively high, considering that the player was nearly half a century old, however, I decided to be open-minded during my visit to the owner. If the condition was as described, perhaps the higher price was justified.

Upon arrival, I found the player set up in the basement. It was connected to power but without an audio signal connection. I was informed that the owner had sold all his original HiFi components and moved on to more convenient Bluetooth devices. The SL-1310 was the last remaining item from the glory days of high fidelity. And although he remembered his turntable to have been in working condition when he had stowed it away some seven years earlier, we found that many of the original functions were no longer intact. The automatic cueing did not meet the start of the record. Instead, the stylus landed somewhere between songs, regardless of the disc diameter setting. We managed to set the speed for 33 rpm correctly, but all attempts failed when trying to stabilise the record speed for 45 rpm. A little confused by the number of issues, we estimated the price of repair, and he offered to deduct these costs from the offer price. Under these circumstances, I was happy to agree to the deal.

Upon connecting the Technics at home, I discovered that the player’s left audio channel failed after a few minutes of playing. I managed turn it back on by re-connecting the cinch cable, but shortly after, the left channel failed again. Unlike our Sansui SR-525, all Technics decks of the period came equipped with non-detachable cinch/RCA interconnects, a factor that made it difficult to locate the left channel’s contact issue and also seemed a hindrance to upgrading the sonic ability of the player. I therefore made a list of all defects and added to this the need for proper cinch/RCA sockets to be installed. Luckily, our trusted mechanic for such audio matters had some time available, and I drove by for a visit the next day.

In terms of product innovation, the SL-1310 carried the direct drive concept one step further than the original designs. While most record players of the time, including the Sansui, had their large motors sitting centrally under the platter, a concept that required a certain minimum height, the revised Technics design used the platter itself as rotor and the player’s chassis as the stator. The turntable could therefore have a lower silhouette, used fewer parts, dissipated less heat, lowered electricity consumption to less than 0,1 watts, and decreased resonances. Speed-accuracy was class-leading at the time, at just 0.1% error over 30 min playing time. It is often said that disc-cutting lathes of the time were less accurate than this. Due to the slow-revolving motor, rumble was found mostly outside the relevant frequency band, namely from 20 - 35 Hz. The two peaks measured are at around 22 and 34 Hz. And of course, the iconic Technics platter showed a wide tapered rim with strobe markings for 33-1/3 and 45 rpm synchronisation at 50 or 60 Hz, i.e. four dotted lines in total.

As it turned out, our SL-1310 was mostly suffering from corrosion to the switches that had accumulated over the years. This was most likely facilitated by moisture while being stored in the basement. We discovered that most switches could be taken apart to be serviced. Only one of them, the one to set the record size, was beyond repair and needed replacement. Two holes were bored into the back of the turntable to hold the new cinch/RCA sockets. This step enabled me to use my own interconnects with this player, a seemingly small improvement but with a major impact on sound. The faulty left channel turned out to be caused by a loose connection inside the Shure cartridge itself. It was decided that we would heat the relevant pin with a soldering iron, until we could push the pin a few millimetres into the cartridge housing. The trick worked, and both channels played music again.

Back at home, I connected the Technics SL-1310 to our office system and was very pleased with the way it performed and handled. I set the 'Memo-Repeat' dial to 'three (3)' and the platter started spinning silently. I then pulled the lever downwards to the 'Start' position. The player reacted by gently lifting the tonearm and setting it down at the start of the first title. I noticed that the placing of the needle could have been a bit gentler, perhaps. However, the small thump it produced was still within reasonable limits. The Shure M75 with elliptical stylus used to be a mid-market cartridge back in the day and could not rival the Shure V15 that was found as standard on German-made High End Dual turntables. However, in typical Shure fashion, the M75 ED put forth a warm and delicate sound with long-trailing decay. It may not have exhibited the bass-slam of the Shure 6S, but it did play accurately and endearingly. It seemed to me that upgrading to the V15 cartridge, perhaps with a Jico replacement stylus would be a welcome but costly alternative for a later day.

The Technics SL-1310 itself could certainly do with some additional decoupling of the chassis. Right from the start, I noticed that any touching of the rack had a similar popping effect as the touching of a microphone. This effect vanished completely, after I placed the Technics on four Oehlbach isolation pads. Since the player is rather heavy with its aluminium platter and aluminium top-chassis, it remains wonderfully stable, despite the inherent softness of the pads. Among the features that I enjoy most about this player are its automatic functions that keep me from having to crawl into the small space under the slope of the roof where our system stands, and its life-like three-dimensional presentation of the music. Paired with our Hafler XL-280 power amp and Tannoy speakers, a deep holographic image of the stage is projected into the room right in front of me. Not bad at all, especially for a deck that is nearly half a century old.

Specifications

-

Type: fully automatic direct drive turntable

-

Platter: 312 mm aluminium diecast

-

Speeds: 33 and 45 rpm

-

Motor: ultra-low speed, brushless DC

-

Motor Power Consumption: < 0,1 Watts

-

Wow and flutter: < 0.03% WRMS

-

Rumble: - 70 dB

-

Tonearm: S-shaped, tubular, 4-pin connector

-

Effective length: 230 mm

-

Effective mass: 23g (incl. 6g cartridge)

-

Effective length: 230 mm

-

Tracking force adjustment: 0,25 to 3g by 0.1g

-

Cartridge weight range: 4,5 - 9g

-

Dimensions: (W) 430 x (H) 130 x (D) 375 mm

-

Power consumption: 8,0 Watts

-

Power Supply: AC 110 - 240V, 50/60 Hz

-

Weight: 9,4 kg

-

Year(s): 1975 - 1977

-

Thorens TD320

Published: 10/03/2022

Manufacturing date: 1986

Author: Karsten Hein

Category: Gear & Review

Tag(s): Turntables

For many years, the Thorens DT 320 headed my list of most desirable affordable turntables, as it already boasted some audiophile features that would only find their way into modern 'High-End' designs much later. When it was first released to the public in 1984, the TD 320 was the top of the Thorens 300-series and was also more generally considered to be top-of-its-class. Early models came equipped with the TP16 MK-III tonearm. Later, this was succeeded by the MK-IV tonearm which was also featured on the model shown here. This places our specimen in the model years from 1986 to 1988. The 300-series was among Thorens’s most successful model ranges and was later extended with some new and revised versions: the TD 325, TD 2001, and the TD 3001.

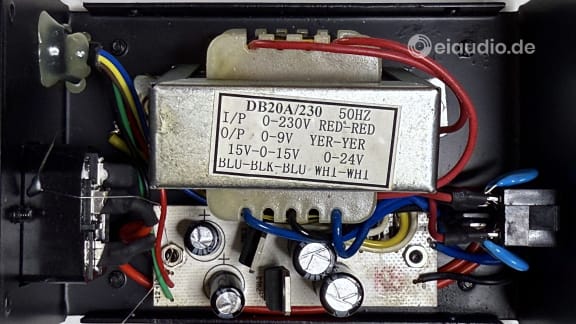

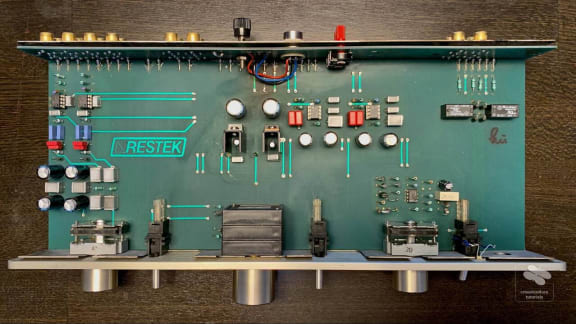

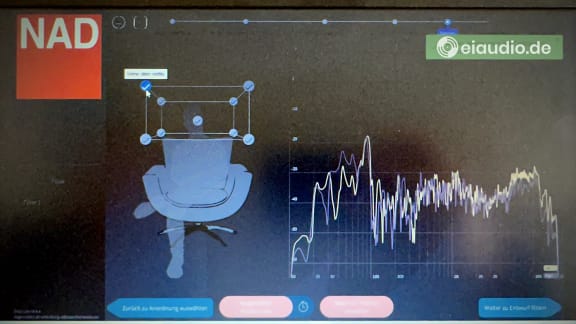

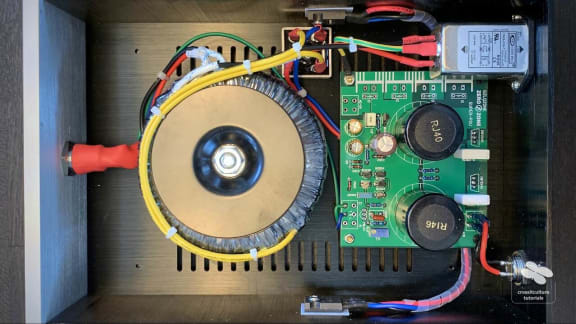

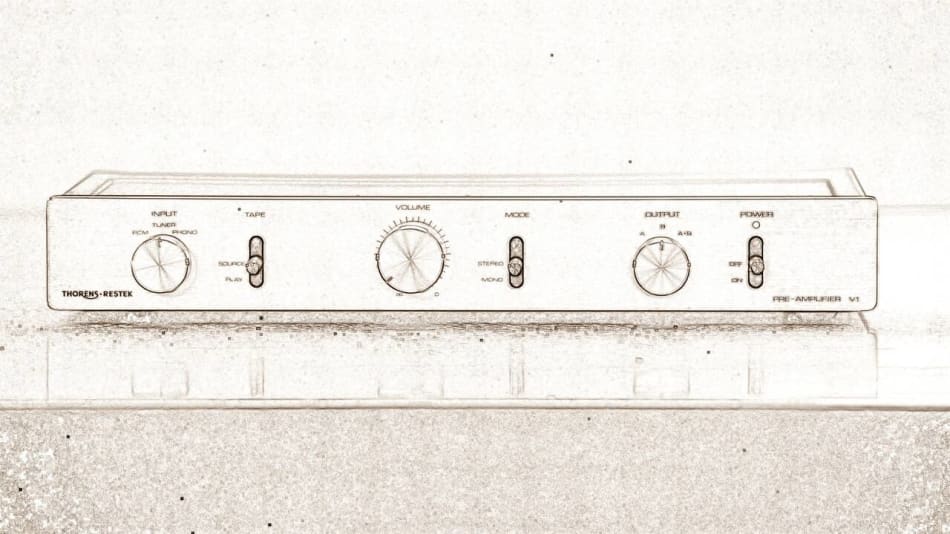

The TD 320 featured a suspended sub-chassis hinged on 3-point leaf springs that held the tonearm and platter separated from the vibrations of the motor. The use of leaf springs proved to be beneficial when compared to earlier coil spring designs, as they limited wobble on the horizontal axis. To eliminate the effect of transformer vibrations, the TD 320 came with a separate power supply. And although the original Thorens supply was simply built into the AC plug, power supply upgrades were among the first and most viable tuning choices for the TD 320. The power supply that is shown here was sold by the French audio distributer 'Audiophonics'. It is of linear low-noise design and has dedicated EMI and RFI filters. Its output is rated at 1.25 A and 16 V. Placing the power supply on a separate shelf-board will effectively eliminate power supply vibrations from the music signal.

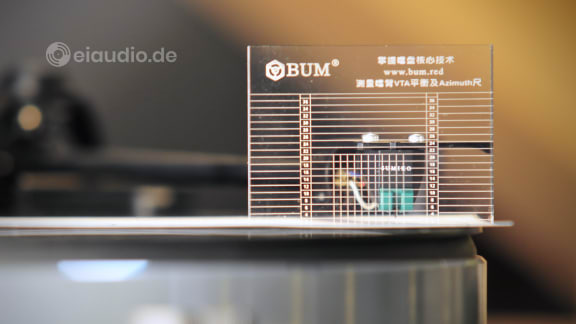

The Thorens TP16 MK-IV tonearm featured adjustable horizontal and vertical bearings to keep the amount of arm play to a minimum. The black dust cap on top of the pivot could be removed to allow easy access to the top bearing. Unlike many of its foreign contemporaries, the MK-IV tonearm came with a fixed headshell that could not easily be swapped around. Its sleve wrapped around the arm’s aluminum tube and was fixed with a single screw. The vertical tracking angle (VTA) of the cartridge and stylus combination could be adjusted by loosening the screw and twisting the headshell into position. There were, however, some flaws with this crude system. For one thing, twisting the headshell on the arm could have a negative or even damaging effect on the fragile tonearm bearings. Second, removing the arm from the overly tight tonearm clamp on a regular basis could negatively affect the VTA setting. And, third, tightening the headshell screw almost inevitably altered the vertical tracking angle again in an unpredictable manner. On the other hand, the arm’s no-frills, anti-skating mechanism could also be conveniently set via a single screw. This affected the position of permanent magnets and actually worked quite well.

When I picked up our TD 320 from a private seller in the Taunus region near Frankfurt, it was in arguably poor condition. Its wood veneer had lost most of its lustre, its dust cover had been deeply scratched. The 3-point suspension had come loose on the inside, and the platter was lopsided and scraping over the plinth with each turn. The drive belt was loose and needed replacement, and the original yellow Linn-branded pickup (made by Audio Technica) had a badly-worn stylus. I placed the Thorens on the back seat of our car and wondered how much time and effort it would take to restore this once great turntable to its original splendour.

I bought a new drive belt from Thakker.eu, fixed and adjusted the 3-point suspension until it held the arm-board at the correct height and level again. I used furniture polish to restore the original wooden shine of the plinth. Following a short interlude with a Sumiko Olympia cartridge (which I ended up sending back to Thakker), I installed our Audio Technica VM95 ML cartridge with a very positive result. Since both the Sumiko and the Audio Technica had a lower body than the original cartridge, I also needed to adjust the tonearm-height for the arm to be level with the record during playback. I replaced the original power supply with the one from Audiophonics and removed the original felt pads under the plinth to replace them with height-adjustable copper spikes. Determined to restore the dust cover, I showed it to my friend Thomas who is an expert on car body work and paint jobs. He offered to sand it down and polish it for me. When he returned it to me one week later, the scratched, old cover looked as though it had come fresh from the shop.

Listening to music on the TD 320 with an Audio Technica VM95 ML cartridge produced a warm, balanced and natural sound. Background noise was low, and channel separation was great. There was a sense of elegant delicacy that was embedded in believable tonality and excellent musical flow. The VM95 ML was a superb tracker and worked well with the TP16 MK-IV tonearm. The Sumiko, on the other hand, had seemed more bottom heavy and much less refined with continuous distortion and sibilance, especially towards the inner groove of records, which was also the reason for me sending it back to the shop. I found that the TD 320 in combination with the Audio Technica VM95 ML lent itself to classical music and Jazz and to those seeking a laid back and insightful sound rather than in-your-face attack. It was perhaps not the most enthralling combination, and I sometimes wondered how a louder and more boisterous Ortofon 2M Bronze cartridge might perform in the balance of things.

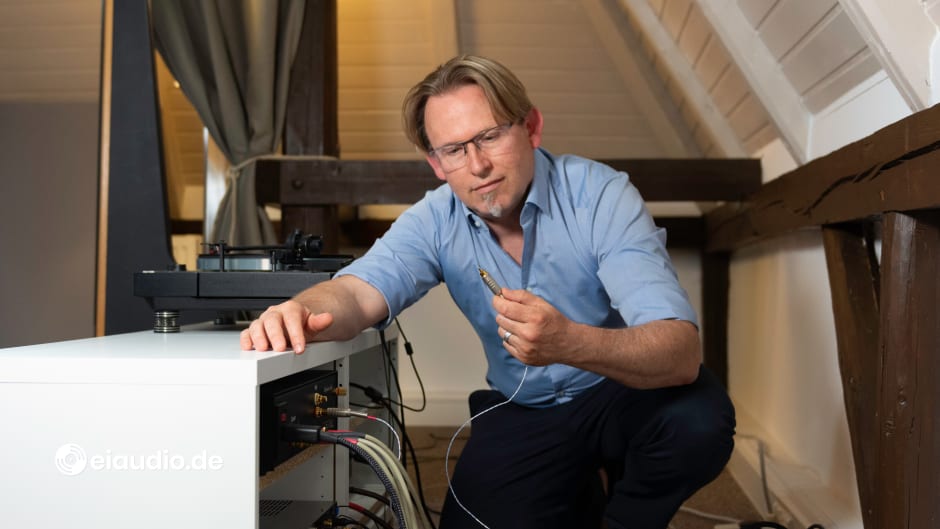

There are still some design flaws to the TD 320 which I might address at a later stage. For example, a look under the hood revealed that the audio signals were in fact running in parallel with some of the power and switching electronics, a circumstance I intend to change for greater dynamics and transparency. There was also the questionable quality of the interconnects themselves that had come pre-installed on the turntable. One could possibly get a better result by changing to a silver solid-core interconnect from our trusted HBS series. Both the platter and the plinth floor might benefit from additional damping matts being applied. The sub-chassis might be re-adjusted to allow for the use of an additional record weight, etc. However, for the time being, I was indeed very happy to have given new life to one of the all-time legends in the world of turntable designs. I understood that there was a lot more fun to be had with the TD 320 than with any of the sleek and modern direct-drive decks from Japan. Although, the Thorens was more complicated to deal with on a daily basis and screamed: Caution, handle with care!

Thorens Company History

Thorens was originally founded in the town of Sainte-Croix, Switzerland, in 1883. Similar to the German Dual, Thorens started out as a specialist for clock movements before producing phonographs from 1903. The company’s first turntables date back as early as 1928. This makes Thorens one of the oldest existing producers of turntables in the world.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Thorens produced a range of sophisticated turntables for private and professional use that continue to be regarded as audiophile High-End equipment. The TD150 MK II was produced for the private market from 1965-1972, and the heavy-built TD 124 was found among audiophiles and studios alike. It was produced from 1957 to 1965.

Following its insolvency of 1999, the newly formed 'Suisse Thorens Export Company' took over the Thorens assets and continued to produce and sell Thorens turntables under the leadership of Heinz Roher. In May 2018, Gunter Kürten took over the company and moved its headquarters to Bergisch Gladbach in Germany. Current models include the TD 124 DD, the TD 1500 with TP 150 tonearm and SME headshell, and the similarly equipped TD 403 DD.

Specifications

- Drive method: one step belt drive

- Motor: 16-pole synchronous motor, 16V

- Platter speed: 33 and 45rpm

- Speed control: 2-phase generator

- Platter: 3.1kg, 300mm, zinc alloy, dynamically balanced

- Wow and flutter: 0.035%

- Rumble: > -72B

- Tonearm: TP16 MK IV

- Tonearm length: 232mm

- Pivot to spindle: 215.6mm

- Effective mass: 12.5g

- Overhang: 16.4mm

- Offset angle: 23 degrees

- Dimensions: 440 x 350 x 170mm

- Weight: 11kg (plus power supply)

- Power supply: Audiophonics LPSU25 (China)

- Supply type: 25VA, linear regulated, EMI RFI filters

- Country of manufacture: Germany

- Year(s): 1986-1988

Let's explore together

Get in touch with me

If you happen to live within reach of 25709 Marne in northern Germany and own vintage Hi-Fi Stereo classics waiting to be explored and written about, I would be honoured to hear from you!

Your contact details

All reviews are free of charge, and your personal data will strictly be used to organise the reviewing process with you. Your gear will be returned to you within two weeks, and you are most welcome to take part in the listening process. Gear owners can choose to remain anonymous or be mentioned in the review as they wish.

Thank you for supporting the eiaudio project.

Audiophile greetings,

Karsten

Phono Preamps

Tuners

Some people will argue that the time of analog radio tuners is over and that there are better ways of receiving signals and processing these into sound. Yet, despite many announcements that analog radio will be phased out from our public broadcasts, analog radio is still the norm rather than the exception. This may have to do with the long signal reach into remote areas that are not yet covered by the digital network, it may have to do with the number of analog radios still out there, and it may also be a strange form of nostalgia.

Be that as it may, it is probably fair to say that the people who support analog radio for the sake of its sonic abilities are few and far between, although they may have a valid point here that should be more relevant than the others. On clear nights, analog sound still has its soft and special charme, simply because there is no translation into digital involved. And because of this, there is an element of a sweet caress to the ears that is more than romanticism in that it satisfied a longing that is very human indeed.

Nikko FAM 600

Published: 20/05/2020

Manufacturing date: 1975

Author: Karsten Hein

Category: Gear & Review

Tag(s): Tuners

Nikko Audio was a division of the Japanese electronics company Nikko Electric Industry Co, which was formed in 1933 in Kanagawa. The company's audio components earned a good reputation, however the brand only reached a limited distribution and during a general decline in the market in the 90's, the division was forced to close.

The history of the Nikko Audio company reads like a rollercoaster ride between a genuine interest in high quality products and inexplicable failure in managing to sell these to the world. The original ‚Nikko Electric Works‘ was re-founded shortly after WW2 as a designer, manufacturer and installer of communication technology and electrical equipment in Japan. In those early years, Nikko mostly manufactured fuses for the Japanese National Railroad - until the daughter of the boss married a young audiophile lad who allegedly had "golden ears" and persuaded his father-in-law to put on a range of HiFi products, a process that began in the late 1960s. The son-in-law understood about good sound, but he was only marginally interested in the marketing of his products, so that he initially developed devices that were very good, but also very expensive and therefore difficult to sell.

With the Audio Division hardly generating enough income for itself in the 1970s, Nikko was forced to revise its strategy and spin off into various foreign subsidiaries. The product range was streamlined and most of the early High End gear was removed in favour of less expensive and therefore more marketable equipment. Although the product quality was easily able to keep up with the competition, they did not perform in terms of sales, which was mainly due to their overly conservative appearance. In contrast to Sony or other big names with their brushed aluminium fronts, Nikko designers could not (or did not want to) follow this trend and therefore had a hard time holding their own in the market.

A later reorganisation of the product range saw the launch of compact equipment in the lower and medium price range. Nikko also entered the German market with these products, among others; they were introduced via various importers and then sold preferably via department store chains or mail order (i.e. the low-cost segment). Soon, a name and products that were still relatively unknown but that had been poised for greatness sold out to the market and the company finally closed business following the general market slump after the Asian flu at the end of the 90s.

The FAM 600 tuner shown here is of elegant design, not only from the outside, but also in terms of the simplicity found within. It came pre-equipped with outputs for quatrophonic users (the big idea at the time) and feels great in the choice of materials. The company’s High End origins still shine through on this device. Although there are better tuners e.g. in the higher Sansui price ranges, this unit offers a great way to experience analog radio at its best. As analog listeners will know, there is radio weather - and then there are those other times, when something is just not right in the universe. On good listening nights, the analog experience, if done right, has all the magic it takes for us to lose ourselves over and over again. connectors.

Specifications

- Manufacturer: Nikko Electric Manufacturing Co., Ltd.; Tokyo

- Product launch: 1975

- Category: stereo broadcast receiver, past WW2 Tuner

- Main principle: Superheterodyne

- Body: Copper chassis, brushed aluminum front, wood case

- Dimensions: 380 x 130 x 300 mm

- Weight: 5kg

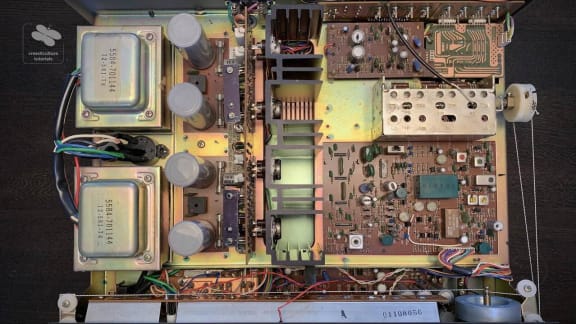

Picture description:

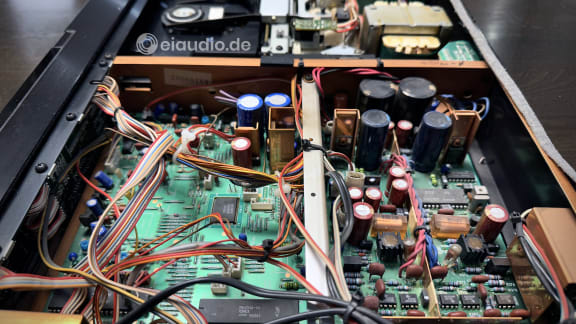

Moving clockwise from top center we can identify the back of the operating panel, the transformer and, below this, the circuit board of the customer made power supply. The 5-pin DIN is located in the bottom right corner, inconveniently just above the power cord. Antenna inputs are in the lower left corner and above these is the tuner's main board. The large tuning rotary capacitor is in the top left of the board. A copper sandwich floor protects the underside of the board from electrical interference with all the internal wiring remaining hidden from view.

CD-Players

The CD offers decent quality music in a compact digital format. It offers a 44.1kHz sampling rate at a depth of 16 bits per sample. The parameters were chosen to cover the full span of human hearing from 20Hz to 20kHz. While this should be enough to replicate most musical information in bits and bytes, in recent times, it is often produced using downsampling and/or bitrate reduction - e.g. when the master file is recorded at 192kHz sampling rate and a depth of 24bit, as is common in Jazz and Classical music. Attempts have since been made to increase the sampling rate and bit depths in formats such as SACD and BlueRay Audio, but these failed to reach a market that had already abandoned the high quality audio sector for high convenience audio, such as MP3 and music on demand services.

It is not surprising then, that sales of vinyl records have recently again surpassed those of CD, the first time in a quarter of a century. With audiophile listeners flocking to fashionable high-res streaming services, ownership has become a rare privilege and is best celebrated and contrasted by the meticulous ritual of playing and storing vinyl. Yet, in midst of all this, there is still lots of fun to be had with CD players, as there is more to setting them up and extracting an audiophile experience from them than may first meet the eye.

To have the most options, make sure that your CD player comes with a digital coax output in addition to the more common Toslink connector, as well as RCA/cinch, of course.

Denon DCD 1500 II

Published: 12/04/2021

Manufacturing date: 1986

Author: Karsten Hein

Category: Gear & Review

Tag(s): CD-Players

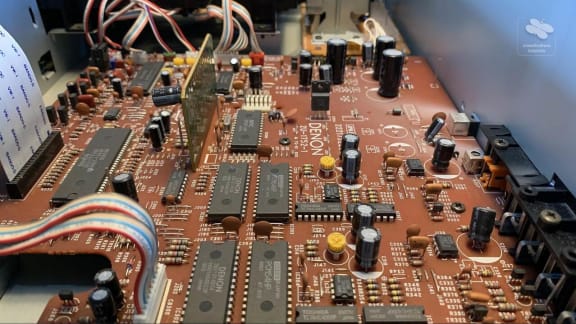

Having owned the smaller brother, a Denon DCD-1420, for some time now, a look under the hood revealed larger placement markings around the smallish capacitors that showed the dimensions of the parts used on ‘the real thing’, namely, the larger DCD-1500 unit. And, although the DCD-1420 is a reliable middle-class player, even after four decades, I have often asked myself, what I would be hearing, had I bought the fully equipped unit instead.

Therefore, when Luigi showed me two CD-players and asked me which of the two to get, I had a strong leaning towards the Denon DCD-1500 II. The photos we saw showed it in good used condition, but they were far from impressive. Both the Denon’s size and design did not give away its exceptional build quality and internal merits. To me, it looked like just another CD player. This impression changed, when I visited Luigi and saw the player, with its display turned on, perched on a proper HiFi rack. Although its size had not changed and its design was still an understatement, there now was a cleaned-up seriousness about it that made me curious at an instant. This was certainly a whole other beast from my 1420.

Luigi played me a few songs on the Denon DCD-1500 II before he switched to vinyl. While I usually cherish the transition from digital to analog, I noticed that I was a little sad to stop listening to the 1500 so soon. Perhaps this was because the player’s cleaned-up looks had been wonderfully present in the music as well. While the player had not sounded spectacular by any means, the music simply had this air of dependability to it that made it endearing to my ears. I had instantly trusted this player to sound pleasant. The lack of this quality is often an issue with CD players; actually, when audiophiles describe devices as sounding analog or warm, it is sonic dependability rather than spectacle that they are referring to.

Luigi suggested I should take the Denon home with me, explore it further and, perhaps, write a review on it, to which I gladly consented. When I was ready to leave and picked the Denon up from the rack, I was surprised by its weight. For a moment, it felt as if it had been glued to the boards. This aspect of the player is so well hidden, it struck me by surprise, despite having read in the advertisement that it was close to 10kg. Coming from a larger and higher built amplifier, the weight would not have surprised me, but from a standard-looking Japanese consumer device, I was positively surprised.

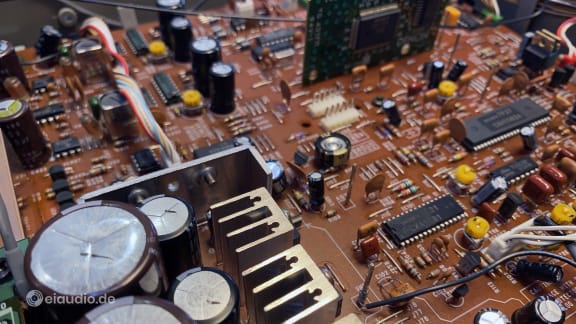

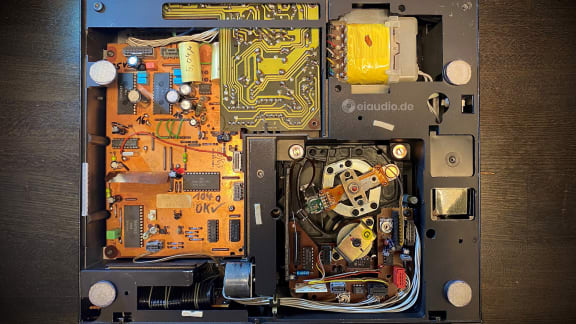

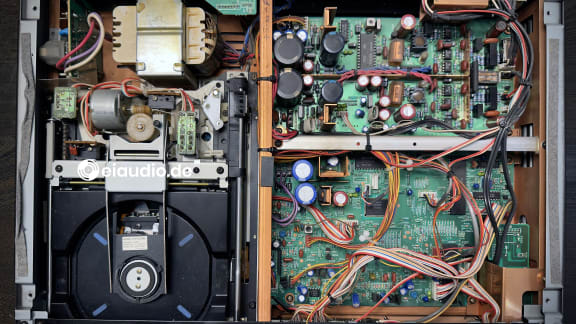

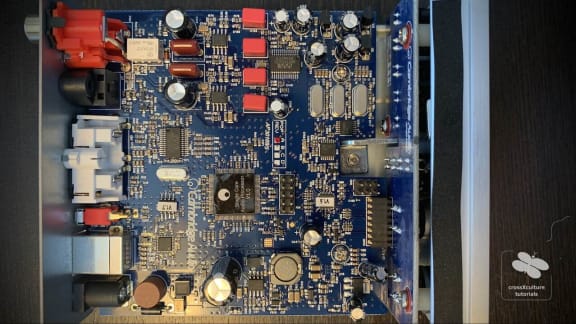

When I came home, I placed the Denon on our conference table and opened the chassis to look under the hood. While the top cover was made of the same bent metal as is custom on today’s units, I did find a 4mm sheet of lead glued to the inside of the cover. This certainly helps to keep the typical drive and chassis resonances at bay and also increases the player’s resilience in case of resonances coming from the outside. I guess anyone could glue a sheet of lead under the cover of their CD players to the same effect, but thinking of my DCD-1420, I could see how pointless that would be, considering that it was not even made of Denon’s full-size parts.

While performing the first operations on the DCD-1500 II placed in our rack, I noticed that some of the buttons on the front were actually made of metal. This has some advantages when it comes to durability. On our silver 1420 for instance, some of the more frequently used buttons have already lost their silver shine. This was not the case on the 1500. Like many of Denon’s players, the 1500 features both a fixed and a variable output which can be convenient in some cases. For any listening test, I used the fixed output to leave out any unnecessary augmentation to the sound. The CD transport is of excellent quality, and the drawer opens promptly and quickly.

In our living room setup, the 1500 had to compete with the 16-years younger 3.7kg lightweight Rega Planet 2000 CD-player, which was our standard choice for CDs. The interconnect used on both devices was a new type of silver solid core with KLE Innovations silver plugs that had been custom made for eiaudio.de and had not been completely run in. This is to say that bass extension had not completely evolved after two weeks of playing. Since this was our best interconnect at the time, I decided that I would stick with this cable despite this small flaw in the setup. The song played was “No Moon at All” on Diana Krall’s ‘Turn up the Quiet’ album.

The Rega came first and played this song with realistic dimension and tonality. I found that timing could at times have been better, with the player showing a slight tendency of dragging its feet, but overall it was an accurate representation with lots of warmth, musical detail, size, and natural space around the instruments. The DCD-1500 II came next and, in comparison, played slightly darker and fuller with a striking three-dimensional richness in Diana Krall’s voice. It did not present the same amount of detail; however, its timing was more accurate with slightly more drive and consistency to it. The Denon came across as slightly more controlled and dryer with individual notes being stopped earlier. The Rega in comparison appeared to be less predictable, was able to present more of the disc’s nuances, gave a fruitier performance and allowed the music more space to perform.

Both players sounded very pleasing, are excellent companions for extended late night listening sessions and renowned for their warm and analog sound. The Denon is surely the mechanically more sophisticated player, whereas the Rega wins its points on the basis of modern DAC circuitry, a more detailed presentation, and lots of musical charm. Considering that the Rega has a 16-year edge over the Denon, the DCD-1500 II a still very good and worthwhile CD-player, indeed. Its build quality, touch and feel, general usability, and its excellent remote control position it well ahead of today’s mid-market competition.

Testing environment: Denon DCD-1500 II (via HBPS pure silver solid core interconnects to) DB Systems DB1 preamplifier; (via Audiocrast OCC and Silver interconnect to) B&K ST140 power amplifier; (via Belden 9497 speaker cables in bi-wiring to) Martin Logan SL3 electrostatic speakers

Specifications

- Digital Converter: 2 x Burr-Brown PCM56P-J

- CD mechanism: KSS-151A / FG-610

- Frequency response: 2 Hz to 20 kHz

- Dynamic range: 96 dB

- Signal-to-noise ratio (1kHz): 103 dB

- Channel separation: 100 dB

- Total harmonic distortion (1kHz): 0.003%

- Wow and flutter: below measurable

- Power Consumption: 17 W

- Line output (fixed / variable): 2 V (max.)

- Headphones: variable output volume

- Extras: RC 202 remote control, variable line output

- Dimensions: 434 x 107 x 324 mm

- Weight: 9.3 kg

- Country of manufacture: Japan

- Year: 1988

Denon DCD-1420

Published: 29/05/2020

Manufacturing date: 1988

Author: Karsten Hein

Category: Gear & Review

Tag(s): CD-Players

Frederick Whitney Horn, an American entrepreneur, started the Nippon Denki Onkyo Kabushikigaisha in 1910 as a subsidiary of the Japanese Recorders Corp. Even before record players, cylinder recorders were common, and Denki Onkyo produced both the media and the players for them. Following mergers with other companies, the name was shortened to DEN-ON which later became Denon. The company was, next to Philips and Sony, a front runner in the development of digital technology and has made a name for itself as manufacturer of professional studio machines as well as HiFi products for the private user market.

The Denon track record of providing new ideas in music reproduction to the world is quite immense. In 1939, Denon manufactured the first (analog) disc recorder for use in the broadcast industry. In 1951, the company played a major role in selling the first long play records to the Japanese population. Two years later, Denon launched a well received line of reel to reel recorders for the broadcast industry. The first Denon HiFi components were launched in 1971. Among them were turntables, amplifiers, tuners, and speakers. In 1999, Denon produced the world's first THX-EX home theater system, in collaboration with Dolby Laboratories. Over the years, Denon has won many prizes for its outstanding contribution to the industry. Recent trends are up to 13-channel multi-channel and wireless multi room systems. Although the company has also produced some outstanding High End components, the bread and butter business has always been divided between their professional line and HiFi products for the broader consumer market.

Some of Denon’s outstanding consumer to High End products were, among many others: the TU 400 Stereo Tuner (1977): the rather peculiar two-coloured PMA 850 amplifier (1977); the DCD-1800 CD player (1985); the by any standard enormous POA-S1 mono power amplifiers (1996), and the Denon DL-103R Shibata cartridge for vinyl fans. The DCD-1420 that is shown here is not listed in the Denon Hall of Fame, as even at that time, there was the more sophisticated (10 Kg) DCD-1520 with better specifications. Despite its non-cult status, I decided to include it here, as it is a great player to begin your explorations in audio. It is well constructed, relatively easy to repair, nearly all parts for the laser drive can still be bought, and the usability is simply excellent. I love the fact that I automatically starts playing when I turn it on and that I can use the numeric keys on the unit to jump straight to the title, even if I do not have the remote at hand. The large display is dimmable and adaptable in content, which is useful for nightly sessions.

Going through the player’s internal DAC, the sound is detailed and leaning towards refined, but it feels a bit light and is lacking the stamina and tonal balance of higher priced units. Since the DCD-1420 has a digital coax connector, one can connect an external DAC, and this is where the fun begins. Putting the player on a base with absorbers and placing a ferrite clamp on the power cord inside the unit as well as outside, have greatly contributed to the musicality of the player + DAC combo. I might be a little biased, however, having owned three of these players over the years. All of them should still be playing just fine, I would assume.

Specifications

- Digital converter: 2 x PCM54HP

- CD Mechanism: KSS-150A / KSS-210A

- Frequency response: 2Hz to 20kHz

- Dynamic range: 97dB

- Signal to Noise Ratio: 108dB

- Channel separation: 102dB

- Total harmonic distortion: 0.003%

- Line output: 2V

- Digital outputs: coaxial, optical