Philips CD 104

Published: 09/02/2021

Manufacturing date: 1984

Author: Karsten Hein

Category: Gear & Review

Tag(s): CD-Players

I first came across the Philips CD 104 in the early 1990s, when a school buddy of mine was looking to buy a used CD player and asked me for support. Since he was a ‘Philips man’, we checked the journals for budget offers from this company and ended up visiting a CD 104 owner to audition his player. At the time, I was used to the soothing amber glow and sleek modern design of JVC players, and the Philips struck me as being smallish in size and particularly ugly. The buttons seemed oddly out of place. And yet—against my advice—my friend ended up buying the unit and seemed rather happy with his purchase. The player was 8 years old at the time, and I must have been around twenty.

Back then, I was still unaware that Philips had been the company to introduce the CD player to the world, alongside Sony, in 1982, or that the CD 104 had only been the company’s second model. And since my friend had carried the player out of the house by himself, I was also left unaware of the seven kilograms in weight that the compact design so cleverly concealed. As far as I could see, my friend had simply paid too much for outdated junk. All the more, I was surprised to see a rather beaten up looking CD 104 perched on a CREACTIV HiFi-rack at a fellow audiophile’s house—in fact, as the only CD player among some famous turntables and amps. “If done well, the 104 has the potential for greatness.” my friend insisted. I was highly sceptical. This was in 2015, the player was 31 years old, and I was around forty-three.

A few weeks after my visit to the audiophile friend, our 5-year-old Marantz SA 7003 CD player quit working for the second time. The first time had been due to belt failure, and this time the laser had settled and could no longer read any medium. I was furious, and we decided that we would sell it broken, fully prepared to take a hefty 500 EUR loss. To us, the Marantz was not worth repairing, as its transport had been rather loud from the very beginning, with the servo correction being constantly in action. Experiencing such poor quality from a well-known brand destroyed my trust in the achievements of modern HiFi. How was it possible, that a more than 30-year old player could read CDs completely without servo noise and access individual titles faster than a 2010 state-of-the-art Super Audio player? How could the old player run for a great number of years without service, while the new unit seemed to break down every two and a half years?

I did some research on CD players and found that modern machines, even High End ones, are of modular construction with standardised and highly integrated circuits. Manufacturers essentially purchase and combine finished modules, box them in some uniform housing and stamp their name on the units. Sadly, this is done without the manufacturer having much influence on the quality of the parts, nor on the unit’s abilities in terms of sound reproduction. For example, I found that the laser on the broken Marantz player had been built by Pioneer and that many products using this type of SACD laser ended up having the same issues. What is the point of buying a Marantz, one might wonder, if the essential parts in the machine come from other manufacturers and are destined to fail? To make matters worse, modular construction often means that items such as transport and control, D/A converter, S/PDIF decoder, clock and perhaps even the output stage are combined into a single module. This scenario does not leave much room for the manufacturer to intervene, augment and improve the sound.

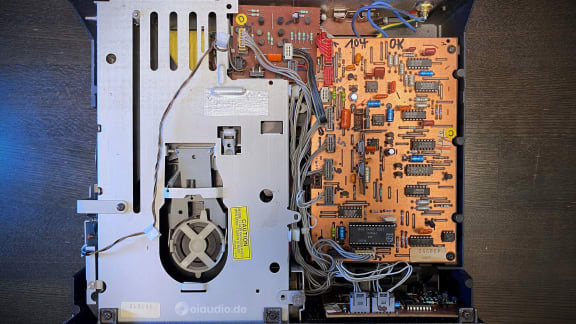

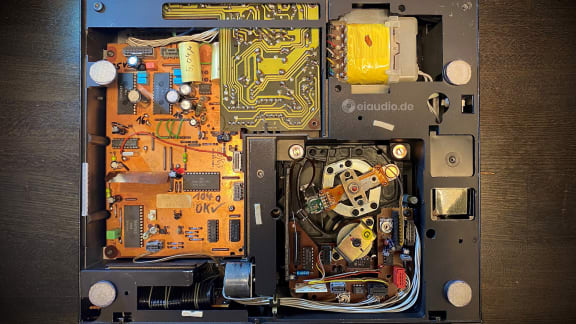

In the late 70s, when Philips set out to build the CD 104, things were quite different. Because the technology was new, Philips had to take full control and responsibility over the whole process. The new technology still had to prove itself to audiophiles with the money to spend. For the offer price of over 2,000 DM, and with few discs available on the market, the vinyl record player was still hard to beat in terms of sound. Philips had to give their new creation all the love and attention they possibly could. The CD 104 has a full metal chassis and includes the CDM-1 transport that Philips developed by themselves. The basis of this is a cast-iron form which holds a sophisticated swing-arm laser paired with six Rodenstock glass-lenses. In terms of musicality, the CDM-1 is considered to be the best transport ever made. Following the audiophile rule of “garbage in = garbage out”, a flawless reading of the source material is the basis for musicality.

While Philips engineers included everything they understood about transport construction to get their first players right, the focus of later players was to make the technology more accessible to the average consumer, and this meant bringing costs down. Iron, metal and glass gave way to plastic. And, since software and electronics are cheaper in production than precision optics, modern CD players will correct the tolerance of mediocre transport optics by using their servo motors and error correction at full capacity. Since these features are on board anyway, they might as well have a job to do, right? Before customers notice the handicap, and before their players fail, the warranty period will have expired. This explains why we could hear the servo motors on our Marantz SA 7003 CD player from the very beginning, and perhaps also why the player failed after a short five years.

When the Philips CD 104 tray opens, the sound, speed, and grace is similar to that of a bank volt opening. I catch myself holding my breath each time, hoping that it will once again make the full journey, just as it has so dutifully done for four decades. The player that Luigi brought by our house for testing has been skilfully reworked and upgraded to combine the physical assets of the eighties with the electronic insights of today. And although we are not quite certain to which extent the upgrade was made, typical improvements include making full use of the CDM-1 transport and the player’s two legendary TDA1540 mono multi-bit DACs by eliminating the digital oversampling and the analog filter in the output stage. Eliminating S/PDIF and jitter, and correcting channel delay. Further upgrades may include replacing the analog output amp from the original 35 transistors version to just two high quality FETs per channel, improving internal shielding, wiring, etc. German mods are currently available from Roman Groß ‘New Perspectives on Sound’ and from ‘KR High End Laboratory’.

From the outside, our unit shows gold-plated RCA/cinch sockets in place of the formerly fixed cable and plugs, as well as a three-prong power socket to allow the connection of a higher quality cord. The finished player not only surpasses its original setup in terms of sound performance, it also beats most of today’s players in terms of tonality, nuance, soundstage, and musicality. If the 14-bit DAC was ever considered to be a handicap by hasty customers, I can assure you that no handicap is audible at all. In fact, the later Philips 16-bit TDA1541 DACs (corrected 31.05.2021: see below) were used in Sony’s High End players well into the 1990s, which says a lot about what Sony thought of the Philips DACs.

Although I was quite sceptical at first, just a few seconds of listening made it clear to me that this vintage player performs well above the level that I was used to from our Marantz CD-17, an audiophile legend in its own right. CD never sounded this good in our house. If Marantz’s CD-17 is best described as sounding ‘analog’ and ‘warm’, I would not even know how to attribute special character to the Philips CD 104 NOS modification, except to say that it sounds —real.

At the time of writing this, the player is 37 years old. And just last night, I showed it to my seven-year-old daughter, and she ended up dancing to an Alin Coen CD.

Specifications

- Digital converter: 2 x TDA1540P

- CD transport: CDM-1

- Frequency response: 20Hz to 20kHz

- Signal to Noise Ratio: 90dB

- Channel separation: 86dB

- Total harmonic distortion: 0.005%

- Line output: 2V

- Dimensions: 320 x 86 x 300mm

- Weight: 7kg

- Year: 1984

NOS Modification

- No oversampling

- No analog filter

- No S/PDIF format

- No Jitter

- Channel Sync

- FET output amp